October 2nd, 2019, Curitiba, I gave a keynote speech at the 25th IUFRO World Congress. For the first time ever Latin America hosted a World Congress of IUFRO, one of the oldest network of international forest scientists, established in 1892. IUFRO Keynote Speech as prepared for delivery[1] Distinguished IUFRO and host institute members, Congress Organizing Committee, and dear delegates: I am honoured to be addressing such an eminent audience passionate about forests and people. I am dedicating my talk to forest guardians including youths, women and diversity. 15 years ago, I was in Brazilian Amazon forests to assess training of non-timber forest produces for indigenous communities. Ever since, I have been here several times, more recently in tres frontera that borders Brazil with Colombia and Peru. One morning I was travelling with Brazil Nut gatherers, known as castañeros. I was told that Brazil Nut fruit looks like a coconut, but it is bigger and heavier. [1] Delivered on 2nd October at Expo Unimed, Main Theatre, Positivo University, Curitiba Before getting out of my jeep one of the castañeros handed me a helmet. They indicated me to wear when we get inside the forest. I declined thinking they wanted me to climb the tree just like we do in India to harvest coconuts. When Brazilians use the word big never under estimate. The Brazil Nut tree is one of the tallest trees on the earth! The fruits fall at an immense velocity. You do not harvest it like coconuts instead you collect Brazil Nut fruits from the ground making it a risky business for human heads. Instinctively, I had put on the helmet just like this girl child in the photo. The story of this photo, as told by the photographer, is that the private company – you see the logo on her helmet – certifies that Brazil Nuts are fair and organic. The company hires migrant families, like her parents, for gathering Brazil Nut fruits. The company’s aim is to pay better wage to the adults so that the children like her can go to school instead of risking their life collecting Brazil nut fruits. This photo is one of the contributions of an open access e-book titled, ‘Landscaping Actually’: Forests to Farms through a Gender Lens’. We launched this e-book at the IUFRO Congress at Lake City in October 2014. (https://issuu.com/ciat-ftagender/docs/landscaping_actually) The idea of this book came up when I was working in Colombia for CGIAR’s Forests, Trees and Agroforestry. I had to do a survey of how people understand forest from a gender perspective. Instead of ASKING questions using Monkey Surveys, I decided to LISTEN to stories from different groups of people. We received some 200 eligible fabulous photos with stories in 18 languages. The book has 40 short-listed photos and stories. This quote aptly summarises ‘All around us people are telling us stories about forests and people. We just don’t listen to them.’ I paraphrased it from this original quote ‘All around us, the plants are communicating. We just don’t notice it.’ It is a quote by one of my distant paternal great-great-grandfathers, Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, a prominent scientist. In 1901, for the first time ever, Bose demonstrated that plants are like any other life form and are sensitive to environmental factors like fire or light.[i] Today, I am going to demonstrate how simplifying science for better communication matters. In the next 15 min: I will first share trends in proliferation of forests for people science; second, how different stakeholders perceive it; and lastly, solutions to minimize discrepancy and ways to improve media visibility of our forest science communication. I would be biased if I would not talk about my maternal grandfather. He belonged to Santhal adivasi of Birbhum district in West Bengal, India.[ii] Adivasis means forest-dwelling indigenous communities. In 1947, the year of India’s independence, my grandfather passed away at the age of 30 without getting recognition of his forest rights. Today, after 73 years of India’s Independence, the fate of 2 million indigenous people’s forest rights continues to be at stake. Next month, the Supreme Court hearing will decide whether many of these 2 million forest communities, including my grandfather’s tribe, will be evicted from their forestland.[1] The good news is that I am standing here because my grandmother and mother lost their forest-dwelling indigenous identity. Not everyone would like to lose his or her access to forest and identity because of deforestation, displacement or for other’s development. We have enough empirical evidences to prove that indigenous peoples and local communities are the best forest guardians. We now need to communicate and communicate in a simple way.

Is it different from indigenous knowledge that exists in forms of stories, folklores, or arts? The indigenous communities in Brazil and Paraguay, for example, have been using Stevia long before scientists, economists and private industries made it a commercially successful plant. Mizo and Karbi indigenous peoples in India are using Alpinia nigra locally known as Tara to treat gastrointestinal diseases. The stories of communities managing medicinal plants and foods from forest need to be acknowledged as indigenous knowledge. Over the centuries our ancestors have been looking for wisdom i.e. the craft of communicating knowledge with experience, while modern science seems to focus on knowledge – facts and information. We cannot do one without the other. Communication is supposed to facilitate the recognition of others, enable social relations and hopefully what Paulo Freire called ‘the practice of freedom’. Every second, on average, around 6,000 tweets are tweeted on Twitter, which corresponds to 350,000 tweets sent per min. More information means more people are voicing opinions and expressing their belongingness. It is either-or.

About 2,870,000 English language scientific publications exist on the topic ‘forests for people’. 1,660,000 are published between 1989-2019 and 17,000 in first six months of 2019. The number differed for different languages Bahasa Indonesia, Spanish, Portuguese and French. Given the diversity of rich indigenous languages we have globally, it is a challenging task to have scientific publications in indigenous languages. On the other hand it is equally rare to see existing linguistic cross-references such as referring to Spanish or French literature for research in English and the other way around. These 2 million research papers shows the significance of forests for people.

In this complexity of categorization of issues I move to the second part to share stakeholders’ perceptions about fact vs. fake forest communication.

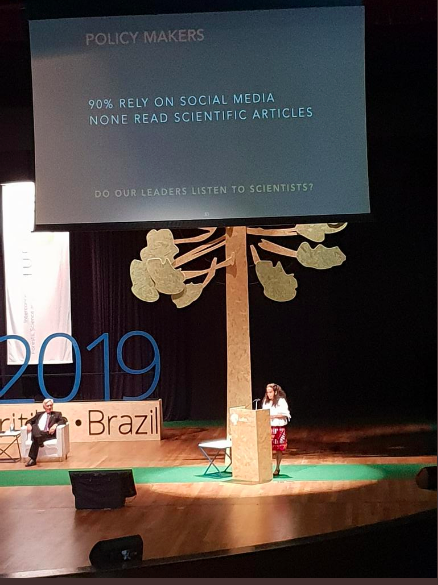

Media Television, prints, documentary films, banners, radio and new technological social media such as Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter are changing the way we are communicating. Social media are often free, easy read in 30 seconds layman language and accessible unlike scientific journals. Anyone who watched Decoding Bill Gates in Netflix knows that his inspiration to do Philanthropy was from one New York Times article written by American journalist Nicholas Kristof. Media is corporate owned and they will communicate what is incentive for them be it plain facts or twisting the facts. Media, for example, can cause damage by focusing only on the problems rather than solutions to forestry issues ranging from legal uncertainty in forest conservation, forest burning or illegal logging. Free or community media often propose solutions such as indigenous forest fire management that is beneficial in forest protection or that extractive industries need free, prior informed consent from the indigenous communities. Policy Makers My second key stakeholder pick is the one we talk about all the time: the policy maker. Our key objective – as a practitioner, think-tank, researcher or student – is to share findings for better policy and implementation. Do our leaders listen to scientists? Interviews with forest policy makers show they depend on Twitter feed; particularly those with trending #hashtags for global forest policy updates. A senior retired forest officer and former member of the legislative from indigenous territory of northeast India mentioned that oil palm plantation is the solution to promote settled farming. The way to achieve it is by cutting down diverse bamboo forests and creating new degraded land for plantations. It is from Twitter that he learnt oil palm could be claimed to get carbon credit. There are many tweets that ‘plantations are not forests’ and ‘tree-planting to carbon offsets is no cure all’ – yet, the tweet that oil palm is an eco-friendly plant gets picked-up by policy makers. We listen to what we want to hear and when we want to hear it! This brings to my next stakeholder – Philanthropists In 1999, I worked briefly with the Tata Trust managing grants and was happy to see that civil societies benefitted from grants to promote community forestry. Today, we see many individual international philanthropists and corporates supporting sustainable development. Although it raises concerns: first, the danger of concentrated wealth with 30 billionaires that is using assets of 3 billion poor, and second they hold influencing power to fund without consulting the community they serve. Last year I interviewed a grant manager of an individual philanthropist in Africa and Asia. According to him, reading this scientific paper in Nature – global tree cover has increased – led him to shuffle the funding by shifting focus from collective forest tenure towards land and housing rights. Social Movements Brazil and Latin America are at the forefront when we talk about social movement. We see across the globe farmer’s marches, save the forest marches, and protect environmental defenders marches. A few years ago I was working in Colombia’s Cauca and Valle del Cauca on forest tenure and agroforestry research, which is a region, you may know, (in)famous for armed conflicts and forest’s proximity for coca plants often located in protected territories such as indigenous reserves. A Human Rights activist had mentioned that criminalization of the legitimate right to protest has become a big hurdle for indigenous peoples to voice their opinion, talk about forest science. It even has cost lives of environmental defenders. The social movements and processes are local communities’ way of communicating wisdom to hold dialogue against deforestation, dispossession and displacements. Women and Diversity Instead of picking up the private sector as the fifth stakeholder (given that big giant corporates Nestle, P&G will miss the 2020 deforestation goals) I will talk about women and diversity. The IUFRO Congresses are the best indicator that women in forestry have been increasingly gaining international recognition. If I understood correctly from Mr. Alexander Buck, Executive Director of IUFRO, women represented about 40% of the registration for IUFRO2019. From my observations, I have seen almost all panels with equal or above participation by women in this conference, which demands for an applause. I am a member of IUFRO’s Gender and Forestry Working Party within Division 6 i.e. Social Aspects of Forests and Forestry. Our team focuses on gender research in forestry, and education, gender and forestry.[iii] Thanks to the IUFRO Congress Organising Committee we organised a sub-plenary, technical as well as poster session on the topic ‘Women and Forest in Tropical Countries’. The notion of women’s equality is misunderstood. Women are agents of change for sure, but to categorise them as a homogenous entity is a miscommunication. Women have hierarchy and categories such as power, colour, age, citizenship, education, property, or leadership. This often fails to get reflected in forest science. As a next step forward for communicating forestry, women and diversity is the key. The third and final part of my talk is identifying communication solutions

I talked about how forest science communication is susceptible to manipulation and misunderstanding. We cannot expect scientists to exert more authority in public discourse or hope that media houses would regulate disproportionate attention to contrarians. I believe that one of the principle ways in which we can overcome the communication challenges is by bridging the contemporary science with the wisdom of traditional forest communities. From the perspective of science ‘you’ do not matter, but what matters is data and methods. Wisdom, on the other side of the spectrum, encapsulates caring, experience and an insight on diverse relationships that is beyond scientific discourse analysis. What also matters, is individual and collective experience. Forest is experienced differently by someone who lives inside the forests from those who go there to study it or say the experience by marginal women against women owner of forest business. I cannot think of any better efficient vehicle than IUFRO given that its members represent multi-stakeholders for facilitating this two-way communication dialogue between science and indigenous wisdom. Three years ago, I decided to make films to document indigenous peoples’ way of life. For 22 months, with my meagre savings, I travelled all over India filming 28 linguistically and ethnically diverse indigenous forest-dwelling communities known as adivasis. Screen the film trailer Vaña Vaasiyon 58 seconds watch it here https://vimeo.com/269947672 You have noticed in the film trailer that I have not used any voiceover. My films are made without any script. This is because we need to hear the voices of the real protagonists in their own indigenous languages and let them tell stories the way they want to narrate. Mr. Chair, I am going to conclude that forest people are not voiceless. They need space to communicate their wisdom and our help to amplify their voice in media. Thank you all for your kind attention. [1] The verdict is out now - after a month - at the time of uploading my speech online. The Supreme Court has asked all the state governments to assess all the claims and provide further information. Next hearing date is on November 26, 2019. [i] Royal Society of London [ii] Bir means Forest and Bhumi means Land (Birhum means Forestland) [iii] 6:08:00 under IUFRO Division 6 Social Aspects of Forests and Forestry

Prof. Björn Hånell, IUFRO Vice President (2014-2019) and Prof. of Silviculture at SLU, Umeå, Sweden was the Chair of this 'Forests for People' theme plenary session.

Prof. Hånell emphasised that, “Reporting our results in scientific journals only is not enough. We, forest scientists, must learn how to inform and bring our findings to ordinary citizen. If not, forest are not for people and without support from public we will lose our significance.” Purabi Bose is IUFRO's incoming Deputy Coordinator of division 6 Social Aspects of Forests and Forestry, which is led by Prof. Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch, and she is also Coordinator of 6:08:01 Gender Research in Forestry (2019-2024) Date: Oct 2, 2019 from 11:00 to 12:00 noon. Co-panellist: Maria Chiara, Urban Forests. Location: Main theatre, Expo Unimed, Curitiba, Brazil For further details kindly visit https://iufro2019.com/guest-speakers/ Want to have a dialogue with Purabi do E-mail her at purabib2 (at) gmail dot com

0 Comments

|

Privacy Policy: We use Google Analytics to collect data to improve the Website. By using and accessing the website you are consenting to use of Google Analytics.

All Rights Reserved. PURABI's PERSPECTIVE

Purabi Bose, Ph.D. Passionate about nature and social policy, Ms. Bose is a mountaineer/ trekker, drummer, polyglot (only ten languages), leads a less materialistic lifestyle and loves traditional cooking & feeding. She is perseverant, and values her freedom of being an independent woman. Ms. Bose is a versatile social scientist and has aptitude for creative communications. A 'people person', her academic background is in social anthropology, environmental science, food science and human development. You might be interested to read her reviews on various cultural events at Culture Call ARCHIEVES

November 2019

CATEGORIES

All

Privacy Policy: This website uses Google Analytics to improve the Website. By using and accessing the website you are consenting to use of Google Analytics.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed